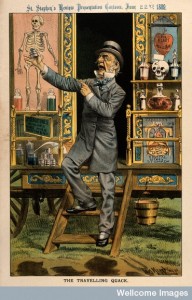

Here’s an editorial from an issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association published 100 years ago (emphasis added):

Here’s an editorial from an issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association published 100 years ago (emphasis added):

One of the cruellest and most despicable phases of the “patent medicine” business is the studied effort made by nostrum exploiters to frighten their victims into the belief that they are suffering from some more or less serious disease. Not content with the sale of their preparations to those who have—or who believe they have—one of the many diseases for which the products are recommended, the “patent medicine” vendors strive to create an artificial demand for their stuff by working on the imagination of the healthy and persuading them that they are sick. The scheme is an old one but none the less disreputable. One of the more recent modifications of this trick is the “gall-stone remedy” fake …

Compare this with a discussion of medicalization by Carl Elliott in his new book, White Coat, Black Hat . After describing how the condition formerly known as “urge incontinence” was repositioned as “overactive bladder” (to remove the stigma), he continues (emphasis added):

Because it is difficult to create a disease without the help of physicians, companies typically recruit physician thought leaders to write and speak about any new concepts they are trying to introduce. “It is always presented as a scientific and clinical opportunity to help patients,” says Peter Whitehouse, a neurologist at Case Western Reserve University. Physicians must be convinced that a new disease category actually describes a patient population whose symptoms warrant a drug. It also helps if the physicians believe the condition is dangerous. When AstraZeneca introduced Prilosec (and later Nexium) for heartburn, for example, it famously repositioned heartburn as gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. But it also commissioned research to demonstrate the devastating consequences of failing to treat it. Once physicians are on board, a company can get a concept like overactive bladder or reflux disease into widespread circulation simply by funding CME [Continuing Medical Education] events, journal supplements, and disease awareness campaigns. “That’s easy,” says Whitehouse. “You just have to have enough money.”

The American Medical Association once complained about rival practitioners who invented new diseases. A hundred years later, medical thought leaders (also known as KOL — Key Opinion Leaders) are paid to promote new diseases.

Is this progress?

Related posts:

Should grief be labeled and treated as depression?

How the pharmas make us sick

Selling drugs like chewing gum

Are Americans naive about medicine?

Resources:

Image source: The Quack Doctor

Suggestion and Nostrums, The Journal of the American Medical Association, September 24, 1920

Carl Elliott, White Coat, Black Hat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine

You ask: “Is this progress?”

In a word – No.

What I am about to say should in no way be construed that I think all medicines are inherently useless or are not all they are cracked up to be.

Many modern medicines like polio vaccine and penicillin are truly wonder drugs and have helped to make humans healthier and live longer.

And I will say up front, I do not suffer any of the conditions I am about to write about. But I have to wonder how many drugs today are superfluous. Does chronic dry eye really need a special prescription only, expensive drop? Is restless leg syndrome really so life threatening that we need another prescription expensive designer wonder drug to treat it?

In some ways modern 21st century medicine is little more than a legal con game in which every layer of the health care industry from Big Pharma, to doctors and nurses, and hospitals participate.

And we wonder why prescriptions cost so much.

Elliott talks about restless leg in White Coat, Black Hat. Until quite recently it was an unusual, somewhat mysterious condition that doctors encountered rarely. In 2005, the drug company GlaxoSmithKline got FDA approval to market its drug for Parkinson’s disease (Requip) as treatment for restless leg syndrome. The press release was titled “New Survey Reveals Common Yet Under-Recognized Disorder – Restless Leg Syndrome – Is Keeping Americans Awake at Night.” The PR campaign implied that insomnia and depression could be symptoms of restless leg, “tormenting” as many as one in ten Americans.

That’s a statistic that undoubtedly has little credibility. I recently read the book Wrong: why experts* keep failing us — and how to know when not to trust them: *scientists, finance wizards, doctors, relationship gurus, celebrity CEOs, high-powered consultants, health officials, and more by David H. Freedman. The author has a thoroughly depressing article at The Atlantic called Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science, where he says “Much of what medical researchers conclude in their studies is misleading, exaggerated, or flat-out wrong. So why are doctors—to a striking extent—still drawing upon misinformation in their everyday practice?” He suggests that as much as 90 percent of published medical information – conclusions that doctors depend on to prescribe drugs and make important medical decisions — is flawed. An expert who studies this problem “worries that the field of medical research is so pervasively flawed, and so riddled with conflicts of interest, that it might be chronically resistant to change—or even to publicly admitting that there’s a problem.”

Sometimes, when I read too much of this stuff – or when I read about what’s going on in politics – I try to think about how much worse things were in the past – the Great Depression, World War II, Sen. Joe McCarthy, the Baptist church bombing in Birmingham. But a friend recently said to me, yes, things may have been bad, but these are our problems, the problems of our time. There’s really no escaping them.